My grandfather lived in a tar-paper covered shack with his young wife and my infant mother while he attended medical school at Columbia College on the GI Bill, and eventually graduated as a cardiologist. In pictures he had a sense of distinguished presence that belied his humble beginnings, and a sensitivity that could be seen but never reached behind his deep reserve. Late in life, his own heart problems came as a surprise, and he underwent a quadruple bypass operation. In the years that followed heart surgery, his personality changed: He acquired a lathe and turned wooden bowls in the shed behind his house, several of which were collected by a Japanese bank. He explained to me that imperfections were a feature, and when a knot fell out of wormy wood, he filled the space with clear resin and crushed gemstones. He took classes in Computer Art, and though he declined with gruff shyness to disclose to me what went on at those affairs, on my last two visits he gave me 8×10 prints of images he had made.

The English language has stock phrases for the heart that vaguely gesture in the direction of the vital organ, but never specify what might be happening therein. One is more likely to receive medication for high blood pressure than any sort of instruction, let alone wisdom, as to the mysteries of the heart’s workings in daily life. We are left to piece together hints from disparate sources, such as findings from the nascent field of neurocardiology, which indicate that the heart has a complex neural network of its own, quite independent from the brain, and that more information originating in the heart is sent to the brain than the other way round, as so often assumed.

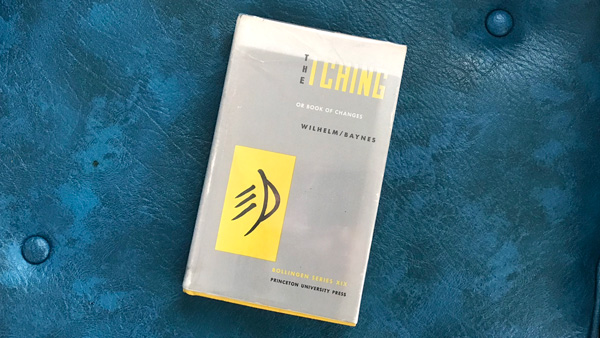

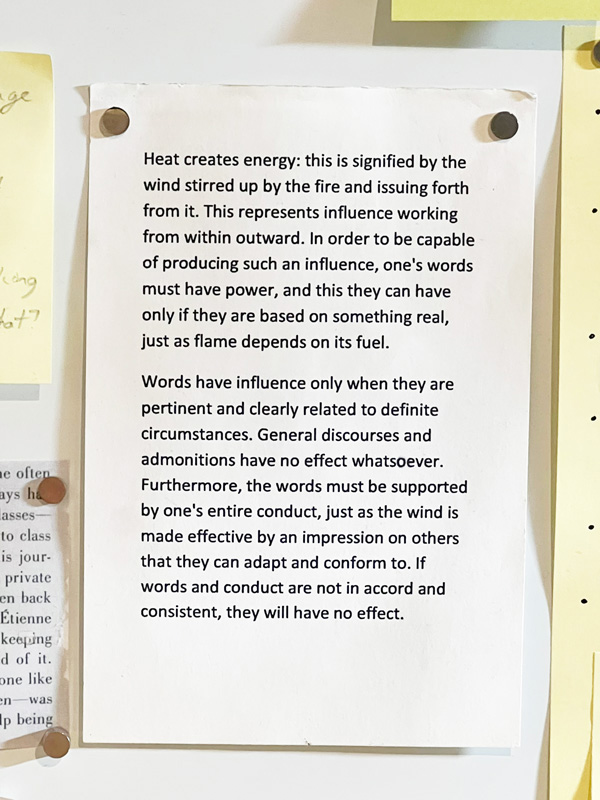

Recently, I wondered if searching the text of the I Ching might yield a different kind of illumination. If you haven’t come across the I Ching before, it’s the oldest of the classic treatises from ancient China and a treasure of a book. As some indication of its priorities, the Richard Wilhelm translation mentions “heart” 63 times, and “mind” but 60. The sifted quotes below are a selection, excerpted from throughout.

“Even with slender means, the sentiment of the heart can be expressed.

True kindness does not count upon nor ask about merit and gratitude but acts from inner necessity. And such a truly kind heart finds itself rewarded in being recognized, and thus the beneficent influence will spread unhindered.

There are secret forces at work, leading together those who belong together. We must yield to this attraction; then we make no mistakes. Where inner relationships exist, no great preparations and formalities are necessary. People understand one another forthwith, just as the Divinity graciously accepts a small offering if it comes from the heart.

The original impulses of the heart are always good, so that we may follow them confidently, assured of good fortune and achievement of our aims.

When a man has learned within his heart what fear and trembling mean, he is safeguarded against any terror produced by outside influences.

If one is sincere when confronted with difficulties, the heart can penetrate the meaning of the situation.

It is very difficult to bring quiet to the heart. While Buddhism strives for rest through an ebbing away of all movement in nirvana, the Book of Changes holds that rest is merely a state of polarity that always posits movement as its complement. Possibly the words of the text embody directions for the practice of yoga.

The heart thinks constantly. This cannot be changed, but the movements of the heart — that is, a man’s thoughts — should restrict themselves to the immediate situation. All thinking that goes beyond this only makes the heart sore.

The root of all influence lies in one’s own inner being: given true and vigorous expression in word and deed, its effect is great. The effect is but the reflection of something that emanates from one’s own heart.

A quiet, wordless, self-contained joy, desiring nothing from without and resting content with everything, remains free of all egotistic likes and dislikes. In this freedom lies good fortune, because it harbors the quiet security of a heart fortified within itself.

When, at the beginning of summer, thunder — electrical energy — comes rushing forth from the earth again, and the first thunderstorm refreshes nature, a prolonged state of tension is resolved. Joy and relief make themselves felt. So too, music has power to ease tension within the heart and to loosen the grip of obscure emotions. The enthusiasm of the heart expresses itself involuntarily in a burst of song, in dance and rhythmic movement of the body. From immemorial times the inspiring effect of the invisible sound that moves all hearts, and draws them together, has mystified mankind.

While man sees what is before his eyes, God looks into the heart. Therefore a simple sacrifice offered with real piety holds a greater blessing than an impressive service without warmth.

Confucius says: Life leads the thoughtful man on a path of many windings. Now the course is checked, now it runs straight again. Here winged thoughts may pour freely forth in words, there the heavy burden of knowledge must be shut away in silence. But when two people are at one in their inmost hearts, they shatter even the strength of iron or of bronze. And when two people understand each other in their inmost hearts, their words are sweet and strong, like the fragrance of orchids.

Here the place of the heart is reached. The impulse that springs from this source is the most important of all. It is of particular concern that this influence be constant and good; then, in spite of the danger arising from the great susceptibility of the human heart, there will be no cause for remorse. When the quiet power of one’s own character is at work, the effects produced are right.”

I Ching, trans. Wilhelm/Baynes. Still no desire to read Shakespeare, yet.

I Ching, trans. Wilhelm/Baynes. Still no desire to read Shakespeare, yet.